| Quantumology |

|

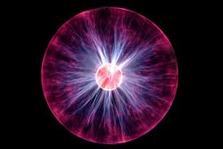

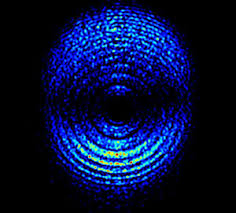

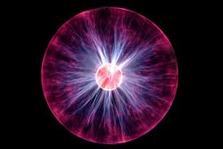

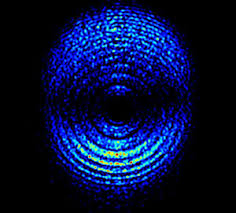

The electron is the thing that makes atoms energetic. Electrons were thought to orbit the nucleus of the atom, the nucleus being a tight bundle of protons and neutrons. Their form has been theorised in many ways, from tiny billiard balls to points of nothingness, but the fact remains - electrons are so small and so active that we cannot tell what they really are. What we do know for sure is that they are negatively charged, and that the atoms of elements (an element is a substance that can't be broken down into any other substance) have a fixed number of electrons within them. In each atom, the number of electrons remains constant, unless or until the atom interacts with another atom. But the energy level of the electron is not constant. Electrons gather round the nucleus in a cloud, like the outer arms of a galaxy gather round the galactic centre, and this cloud is known as the electron shell. Atoms have various levels in this shell which its electrons can occupy. To visualise this, it is said that the further away from the nucleus an electron is, the higher its energy level - the closer it is to the nucleus, correspondingly, the lower its energy level. According to physicists, electrons share an all-time goal - to be close to the nucleus, at the lowest energy level possible, and the lowest energy level possible for a physical system is called the 'ground state'.  Unfortunately for the lazy electron, which by the way is negatively charged, there are a lot of photons around. Now it seems fair to say that despite the assertions of physicists, not all electrons are lazy. Some are probably quite adventurous, and for them the presence of photons is a positive boon. Because in order to change its position in the shell, to move from one energy state to another, the electron relies on photons. To lift up to a higher level, it has to 'take up' or absorb a photon, and to drop a level, it has to shed one. The photon is a particle of light. Not necessarily a visible particle of light, for photons come in many packages - from gamma rays to infra red, the entire electro-magnetic spectrum is made of them. It seems that electrons are not fussy about the kind of photons they throw around. We have a similar relationship with light. When we are feeling glum, it's a good idea to get out in the sun. We have bright moods, dark places, sunny dispositions and black looks. Our language asserts this relationship with light because it is as real to us as it is to the electron, and funnily enough it does very similar things. We have one body, which we might call a shell. Within that shell we have a number of energy levels to play with. Some people have more variations in their energy levels than others - we might be tempted to call people with the greatest variants 'bipolar'. But the similarity doesn't end there, with our absorption or loss of light. Oh no.  We also have a tendency to use the words 'positive' and 'negative' to describe these moods we get ourselves into. We know, even though we don't always like to admit it, that we have some control over these moods and can get ourselves out of dark places if we really want to. But the trouble is, very often we find we don't want to. There's some reason why we should stay there, feeding ourselves with negative thoughts. (And if we think hard about that, we find another correlation with that negative electron busily busting a gut to get close to ground state.) We might use all kinds of excuses for this, the most common one being that it's somebody else's fault we're in the horrible situation causing us all this stress. When an atom gets excited, it's often because an outside influence - usually another kind of atom - has come along and disturbed its equilibrium. Then the electrons are zipping around wondering what to do with themselves and they jump from atom to atom, sometimes getting lost altogether in the process (this is called 'ionisation'). But at the end of the day, they are still the same electrons, whatever state they may find themselves in, and they have an existence to be getting on with. We still don't know very much about the existence of an electron, and one bright spark named Richard Feynman even suggested that there is only one electron in the whole Universe, running rings round time and being everywhere at once. Whatever the truth may be, our relationship with electrons is perfectly clear - its a relationship of behaviours. This, and many other synchronous correlations our beings have with quantum particles, is at the heart of Quantumology.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorKathy Ratcliffe has studied quantum mechanics since 1997 in a life surrounded by birds and animals, She's a metaphysicist, if such a thing exists, looking as we all are for the inevitable bridge between humanity and particle physics. Archives

April 2023

Categories |